Who Killed Melissa Koontz? Was it Serial Killer Tommy Lynn Sells?

Free The Innocent

Help Us Solve This Case

Melissa Koontz, 19, was home on summer break, having completed her first year of college when she disappeared on June 24, 1989. She was working as a cashier at Cub Foods, on the far southwest side of Springfield, Illinois, where she was last seen alive. She clocked out when her shift ended at 10 p.m. Wearing a peach floral skirt and a black short sleeve button down V-neck collared shirt, she passed through produce and grabbed a peach on her way out. The cash register recorded the sale at 10:05 p.m.

It was a prosperous side of town, with new subdivisions and retail stores popping up, expanding the city limits. On the edge of town, surrounded by farm fields. A crime like this was rare, on any side of town.

An hour later, the young woman’s black Ford Escort was found abandoned on a two-lane county highway with fields of soy beans on both sides of the road, about 15 miles away from where she worked. The vehicle appeared headed in the direction of Melissa’s home in Waverly, Illinois. A small rural farm town, another 10 miles down the road in Morgan County.

A couple returning home to Waverly after attending a wedding in Springfield nearly collided with the black Ford Escort, as it slowed to a stop. After seeing the same vehicle on the news, and hearing the story of the missing woman, Ann Bramblett called police to report what she had witnessed. “Ann stated that the vehicle upon stopping in the roadway had to be passed by her companion to avoid striking the vehicle,” read a detective’s report.

A person living across the street noticed the car parked in the southbound lane with its headlights on. With a posted speed limit of 55 mph, the parked vehicle on the roadway posed a hazard for approaching vehicles speeding upon it.

A Sangamon County Sheriff’s deputy arrived on the scene, activated his emergency lights as a precaution, ran the license plates and approached the vehicle. The car was owned by Robert Koontz, Melissa’s father. The keys were still in the ignition. A woman’s purse was on the passenger side floorboard. Inside was a wallet that contained credit cards, a small sum of cash and the driver’s license of Melissa Koontz. The deputy called her father and moved the vehicle off the roadway. There was no sign of Melissa and nothing to indicate any sign of a struggle.

A suspicious person loitering in the parking lot

The deputy radioed his supervisor. “The only other remote thing I could think of would be to have someone go to Cub Foods and just see if anything out of the ordinary happened.”

As the investigation progressed, detectives from the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Department identified a number of witnesses who observed a suspicious white male in his 20s, with brown hair, approximately five-foot-ten inches in height, with a thin build, lurking in the employee parking lot around the time when Melissa exited the store. He was holding what appeared to be a liquor bottle, loitering near the backside of the grocery store.

One woman who was walking in the parking lot “felt that someone was watching her.” The woman observed the man standing between two cars. A detective noted in his report, “He did not appear to be getting in or out of any of the cars. His stare made her feel uncomfortable and she avoided eye contact.”

Another couple driving through the employee parking lot observed a man seated behind the steering wheel of a black colored vehicle with a woman in the passenger seat. They told detectives, “The occupants were facing each other and tried to duck down when his headlights illuminated them.” They appeared to be engaged in a heated argument.

Sherlock Holmes would call that a clue as to what happened.

But who was this suspicious person?

Donald “Goose” Johnston

With her piercing blue eyes staring into the lens of the camera that snapped her picture for her senior high school yearbook, smiling with her whole life ahead of her, Melissa’s life was now reduced to a missing person poster.

Four days after Melissa disappeared, an intellectually disabled alcoholic, named Donald Johnston, known as “Goose,” saw the missing person poster on a clip board while inside the squad car of a Macoupin County sheriff deputy.

Donald “Goose” Johnston agreed to a video recorded interview by PI Bill Clutter on July 20, 2008.

Like a scene from Mayberry, Carlinville, Illinois’ version of Otis was given a ride home by a deputy who discovered Goose walking late at night on a rural country road. Goose lived in Carlinville, the seat of Macoupin County, 45 miles south of Springfield. The deputy noted in his report that “Goose” claimed to have seen the missing woman around noon that day in Carlinville.

The date was June 28th. Police had received hundreds of tips, and this one came from an unreliable source. Goose had identified the names of the people who were with him when he allegedly saw Melissa alive. Presumably, they were spoken to, but nothing more appears in any of the law enforcement reports about this.

A few days later, on July 2nd, a woman jogging stopped to relieve a full bladder and ducked into a cornfield, only a few miles from where Melissa was last seen alive. There, she stumbled upon the corpse of a badly decomposed human being. The location was exactly 2.5 miles west of Cub Foods. A right turn out of the employee parking lot. And a left turn at the next crossroad. The body of Melissa Koontz had been found. An autopsy placed her time of death on the date she disappeared.

Goose Johnston’s claim of seeing her alive in Carlinville four days after she went missing was clearly bad information.

There were telltale signs she had been sexually assaulted. She was laying on her back, and her peach floral skirt had been folded up, covering her abdomen. She had been stabbed to death with a knife that penetrated both the inside of the rolled-up skirt and her V-neck shirt. Her underwear was torn. The top buttons of her V-neck blouse had been violently ripped away and the front clasp of her bra was torn open, exposing her breasts. All that was left was her breastbones. Exposed to the elements more than a week in the sweltering heat of summer, much of her flesh had been consumed by maggots. It was a grisly, foul sight. Any bodily fluids left by her killer from the apparent sexual assault was consumed by bacteria and vermin.

Now a homicide investigation, the story dominated local news coverage. Goose encountered that same deputy again at the Carlinville police department, about a week after Melissa’s body was located. Goose was under arrest for stealing a woman’s wallet from her purse inside a local tavern.

Intoxicated, Goose blurted out that he knew who killed that girl, the one he saw on the missing person poster. It was Tom McMillen, he declared. McMillen was someone he knew well. They often drank among a group of other acquaintances. Surprised, the deputy asked Goose how could he be certain it was Tom McMillen who killed her? Goose replied, “I was there, and I watched.” The deputy inquired, how did Tom kill her? “Tom choked her to death,” said Goose.

This of course, was not the manner of death. She had been stabbed to death rather than strangled.

A series of one lie after another

The Sangamon County Sheriff’s Department in Springfield, two counties north of Carlinville, was the lead agency investigating the homicide, since her body was found just outside the city limits. Detective James Mitchell was contacted shortly after midnight on July 9, 1989. According to Mitchell’s report, he was informed by the deputy in Macoupin County “that Mr. Johnston was very intoxicated and appeared to be a little 10-96” [police code for mentally ill]. Detective Mitchell waited to interview Goose to give him time to sober up.

Once he had done so, Goose had forgotten all about what he said when he was drunk. He said he knew nothing about a murder. He had seen the girl’s picture on a missing person poster, and that’s all he knew.

He was interrogated over the course of many hours and several days. The next story he gave was that he was driving with Tom McMillen and five other people when their car ran out of gas. They all started walking down the road and flagged down a car driven by a young woman.

Det. Mitchell noted, “After talking to Don Johnston his story changes once again.”

The next story Goose gave was that he and his 15-year-old cousin, Danny Pocklington, were walking from Carlinville in the direction of the town of Waverly. A distance of 26 miles from Carlinville, why in the world would they be walking to Waverly? Yet, Goose claimed while walking to Waverly, a man named Gary Angelo pulled up in a pick-up truck and gave them a ride. As they were driving, Angelo saw Melisa driving by in her car and declared “I’m going to kidnap that girl.” Goose said Gary Angelo stood in the middle of the Waverly Blacktop Road and waived his hands in the air. After she stopped her vehicle, Goose claimed that Angelo then pulled Melissa out of the car and Goose said he witnessed Angelo stabbing the girl to death.

One, at that time of night it would have been impossible to tell whether a man or woman was driving toward them.

And the other problem with Goose’s story was the eyewitness, Ann Bramblett. She saw no one standing in the middle of the road waving the car to stop. What Goose was saying made no sense at all.

Goose’s story changed once again, this time, interjecting the names of Tom McMillen and his friend Gary Edgington instead of Gary Angelo. And instead of running out of gas, the story changed to flagging down the first car they saw to commit a robbery because they had run out of beer and needed “beer money.” Yet, there was no evidence of a robbery.

Det. Mitchell noted in his report asking Goose, “why he had fabricated a previous story?” There was no good answer to that question.

And the more he talked, the deeper Goose sank into the quicksand of what we call our system of justice.

In Goose’s last statement, he said yes, he did own a knife. A pocketknife that he often used to scrap the grime from under his fingernails. Detectives got him to admit that he was seated next to Melissa in the backseat and that it was possible he “accidently” stuck her with his knife while cleaning his fingernails. After making that statement, Goose was arrested and charged with capital murder.

A psychiatric exam was ordered by the judge, based on observations of Goose in court during his arraignment. A report submitted to the court found Goose was not competent to stand trial. Goose’s attorney then negotiated a plea agreement to a fifteen-year sentence for his cooperation. His dubious claim of being an “eye-witness” led to the arrest of Tom McMillen and Gary Edgington, who both faced the death penalty.

Perhaps, it was residual doubt that a jury spared their lives, for such a heinous crime. They were given life sentences instead.

The jury that convicted them did not hear testimony from the witnesses who observed a creepy person loitering in the employee parking lot as Melissa exited the store, or from Ann Bramblett, whose testimony would have disputed Goose’s trial testimony that McMillen and Edgington stood in the middle of the road waving the car to stop.

Parallels to the Nicarico Case

In 2008, after starting what is now the Illinois Innocence Project at the University of Illinois at Springfield, I came across a letter from Debbie Hudson, the sister of Tom McMillen. Some 17 years had passed since her brother’s conviction when she read about our work that freed Herb Whitlock from prison that year. Whitlock was unjustly confined behind bars for 21 years.

I was immediately interested in pursuing the McMillen case. I had always been skeptical of the stories I had read in the State-Journal Register when prosecutors in Sangamon County charged Goose Johnston with the death penalty. The stories described Johnston as mentally slow.

At the time of McMillen’s conviction in 1991, I was working on the Nicarico case. My client, Alejandro Hernandez, like Goose Johnston, was also intellectually disabled and had falsely confessed to being a witness to a murder. In that case, the victim was 10-year-old Jeanine Nicarico, who was abducted from her home in Naperville, Illinois in 1983. Her bludgeoned body was found a few days later in a wooded area miles away from her home. She had been sexually assaulted, as well. Hernandez claimed to know who killed the girl after hearing about a reward for information.

DuPage County sheriff’s detective John Sam was assigned to investigate the constantly changing stories of Hernandez. After Hernandez was charged with the death penalty in 1984, Sam continued to investigate the case, convinced that the real killer was still roaming the streets. Sam finally resigned as a police detective rather than participate in the prosecution that charged three innocent men.

Later, a serial killer by the name of Brian Dugan gave a detailed video recorded confession that he alone was responsible for the murder of Jeanine Nicarico, which was corroborated by an investigation conducted by the Illinois State Police. And by 1988, DNA from seminal fluids left by the killer was matched to Dugan, the first use of DNA in Illinois to exonerate someone wrongfully convicted in a death penalty case.

Yet, prosecutors in DuPage County resisted their ethical responsibility to seek justice in the face of this new evidence that challenged the integrity of the convictions of Hernandez and his co-defendant Rolando Cruz. A jury failed to convict a third man, Stephen Buckley.

Seven police and prosecutors from DuPage County were ultimately indicted by a special prosecutor, known as the DuPage 7 after it was revealed that detectives had fabricated evidence that led to the conviction of Rolando Cruz. It was one of the few cases in the history of American jurisprudence that prosectors and police were charged with a crime for sending innocent people to prison.

I saw parallels between the two cases. Both involved persons who were intellectually disabled that led police down the wrong path.

The investigation of the McMillen case

As director of investigations, I assigned two students, Jennifer Donnelly and Jennifer Kirschbaum, who commuted from Peoria to Springfield to attend a Wrongful Convictions class at UIS I co-taught, to analyze the ever-evolving statements of Goose Johnston. The spreadsheet they produced was the best work I had ever seen from a team of students. I was convinced after reading their analysis that Johnston’s story, which changed by the hour as he was being interrogated, interchanging one false statement with another, was a classic false confession.

Another team of students, Priyanka Deo and Sarah Wellard, accompanied me to Carlinville to meet Tom McMillen’s family, which consisted of his mother, his brother John and his sister Debbie who wrote asking for our assistance. His mother and brother have since passed away.

It was a Sunday morning on July 20, 2008. By happenstance, we pulled into a gas station and spotted “Goose” Johnston entering the convenience store early in the morning. After introducing myself and the two students, Johnston agreed to be interviewed. The owner of the gas station graciously offered his back office, where I conducted the interview which was video recorded.

Johnston admitted that he had no involvement in the abduction and murder of Melissa Koontz. That Tom McMillen was innocent and so was his co-defendant, Gary Edgington. That interview was followed by a forensic interview by Dr. Richard Leo, one of the leading experts on false confessions, which was also video recorded. Leo concluded, indeed, in his professional opinion, that this was a false confession.

During his trial in 1991, McMillen’s attorney requested an order from the court to release the mental health records of Johnston, which was denied. However, during our initial meeting, Johnston cooperated by signing an authorization to obtain his mental health records. The students obtained his mental health records from McFarland Zone Center which revealed a full-scale IQ of only 54, well below the level of 70 defining someone as intellectually disabled.

In a 2014 ruling Atkins v. Virginia, the US Supreme Court recognized the inherent unreliability of confessions by someone who is intellectually disabled. The Court wrote, “These persons face a special risk of wrongful convictions, are often poor witnesses, and are less able to give meaningful assistance to their counsel.”

AFIS

Our investigation then focused on identifying the person who left a latent thumb print on the rear-view mirror of Melissa’s car, which did not match Melissa or anyone in her family. The CSI who processed the black Ford Escort conducted a thorough investigation in an attempt to identify the person who left that thumb print. At the time, it was the only physical evidence that police had to work with. Great efforts were taken to have the FBI compare that print with known criminal offenders, but nothing turned up.

I arranged a meeting with the Sangamon County Sheriff Neil Williamson, who had gained local fame for his frequent appearances as the spokesperson for Crime Stoppers in public service announcements on TV. I felt confident that whoever abducted Melissa in the employee parking lot of Cub Foods had driven her car to the scene where she was killed in the cornfield and to the location where her car was found abandoned near a rail crossing. We asked the Sheriff to run the prints in the Automated Fingerprint Identification System, known as AFIS, an advancement in technology that was in development at the time of the initial homicide investigation in 1989.

Our prime suspect was Dale Lash, a serial rapist, who had abducted Lori Hayes, 25, from a strip mall parking lot, not far from where Melissa Koontz was abducted, ten years earlier. Police suspected he may have been a serial killer, as well. Lash, 36 at the time, drove Hayes’ car to a cornfield, sexually assaulted her and shot her in the back of the head and returned her car to a parking lot next to a movie theatre. Before exiting the vehicle, he rolled down the windows and left the mother’s nine-month-old daughter Alexis in her car seat, where she was found alive.

A few weeks later, Sheriff Williamson informed us that they had identified the person who left that thumb print. It did not match Dale Lash, who was serving a life sentence for the murder of Lori Hayes. Instead, the print matched a man named Michael Downey, a friend of Melissa’s brother. Years later, his fingerprints were entered into AFIS at the time of his arrest on a misdemeanor charge. He claimed that Melissa and her brother both drove the vehicle and that he must have driven the car a few days before she disappeared.

DNA Testing of Melissa’s Clothes

Undeterred, I was determined to pursue touch DNA testing, after learning about the exoneration of Tim Masters in Ft. Collins, Colorado. He was 15 when he came upon the body of Peggy Hettrick one morning while walking through a field, a short-cut, to his bus stop on his way to school. Tim Masters was freed from prison in 2008, after a team of forensic scientists from the Netherlands, Selma and Richard Eikelenboom, pioneered the use of touch DNA. In the case of Hettrick, the killer had dragged the woman’s body by gripping the fabric of her clothing, which had been stretched. Using a technique of applying tape to those areas of her clothing that her killer likely touched, the Eikelenboom’s were able to lift skin cells shed by the killer. As few as only 10 skin cells were needed to develop a DNA profile. The results of this process identified the DNA of a former boyfriend, who had been on a short list of suspects, found on multiple areas of the victim’s clothing.

With that in mind, I co-wrote the largest grant in the history of UIS that awarded $670K in 2010 to establish a post-conviction DNA testing program in Illinois to enable us to test the clothing of Melissa Koontz. My analysis of the crime scene evidence suggested that the killer was the one who tore the buttons from Melissa’s blouse while ripping open her bra. There was a very good chance of finding skin cells shed by the killer on the bra.

Melissa Koontz’s clothing was submitted for touch DNA testing.

Free The Innocent

Help Us Solve This Case

Springfield attorneys Stan Wasser and Howard Feldman agreed to work pro bono to file a motion for post-conviction testing to prove actual innocence. That enabling statute cited in the motion was enacted in 1997, spearheaded by Larry Marshall, the law professor at Northwestern University law school who represented Rolando Cruz in the appeal of his death sentence in the Nicarico case. It was that case which inspired Marshall to have law makers enact the statute as a reform to free innocent people from prison through forensic testing.

After that law was enacted, Marshall began plans to establish the Center for Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern law school and I began to plan for the establishment of a similar program at the University of Illinois at Springfield.

Apparently uninterested in knowing what it may reveal, the state’s attorney of Sangamon County, John Milhiser, opposed the petition to have DNA testing conducted on the clothing of Melissa Koontz. The presiding judge disagreed and granted the motion in 2010. The clothing was transferred to a private lab for DNA testing.

The Innocence Project entered its appearance to represent Gary Edgington, McMillen’s codefendant, after I made a trip to New York and provided them with a copy of the petition for DNA testing that was filed by the law firm of Feldman, Wasser, Draper and Cox.

Testing revealed a partial profile of an unknown male from the lace portion of the bra. Tom McMillen and Goose Johnston were excluded based on this partial profile. Yet, McMillen remains in prison today.

The results were inconclusive as to Gary Edgington. Similar to the first round of DNA testing that was performed in 1988 in the case of Rolando Cruz, cited as the first DNA exoneration in Illinois in a death penalty case. Although that testing in the Nicarico case was a full profile match to serial killer Brian Dugan, the results were unable to exclude Rolando Cruz when first tested. Cruz was finally freed from prison years later, with the evolution of more precise DNA testing that eliminated Cruz as the person who raped and killed 10-year-old Jeanine Nicarico.

Tom McMillen DOC photo.

Gary Edgington DOC photo.

DNA testing also eliminated Dale Lash, the person who abducted and killed Lori Hayes.

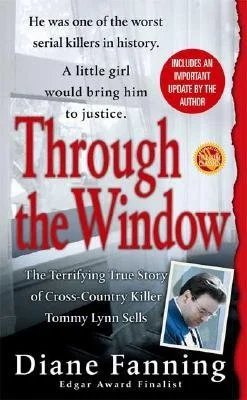

Perhaps, the suspicious person who was seen lurking in the employee parking was someone like Tommy Lynn Sells, a notorious serial killer who lived nearby in St. Louis and was known to roam the country killing over a twenty-year period before he was finally caught in Del Rio, Texas on New Year’s Day in 2000. Sells was 23 years old, thin build, brown hair, and was known to loiter while drinking alcohol, matching the description of the suspicious person who was seen in the employee parking lot at the time Melissa disappeared.

However, his DNA has never been compared to the partial profile that was recovered from Melissa’s bra.

The other crimes of Tommy Lynn Sells that sent innocent people to prison

Booking photo of Tommy Lynn Sells taken Jan. 1, 2000, following his arrest in Del Rio, Texas for the murder of Kaylene Harris. He was caught after a survivor gave police a description of the assailant that led to his arrest.

I began investigating Tommy Lynn Sells in March of 2000, after reading a story in the Associated Press about his confession to the horrific quadruple murders of the Dardeen family that happened in Southern Illinois in November of 1987, in the town of Ina. When I read that story, I was investigating the case of Randy Steidl who was convicted of capital murder in nearby Paris, Illinois. I knew from my investigation that the two cases were connected.

Sells’ confession to the Dardeen murders was corroborated based on details he knew about the crime scene that only the killer would know, according to a report from the Texas Rangers.

The husband, Keith Dardeen, was found in a field a mile from his home. He was shot execution style in the back of the head. His wife Ruby and his three-year-old son, Peter, were found inside the family home lying next to each other. They were bludgeoned to death with a baseball bat that was found in the mother’s birth canal. Ruby was near full-term when she delivered her baby during the ordeal, who also died of blunt force trauma. I learned from the mother of Keith Dardeen that she was told by investigators that Ruby and her three-year old son had remnants of duct tape left around their wrists that was removed by the killer or killers.

My analysis of the crime scene is that Sells, and likely another accomplice, entered the home, subdued his victims, and waited for Keith to come home. Held at gun point, he was likely made to watch the brutal attack on his wife, son, and the newborn baby. Keith was then driven a mile from the scene, where he was killed, and the family vehicle was driven down Interstate 57, and parked with blood inside the vehicle within sight of the courthouse in Benton, Illinois.

The year before the Dardeen family was slaughtered, I was working on the defense of a man who was tried in the federal courthouse in Benton, Illinois, 17 miles south of Ina. It was a massive drug conspiracy case with multiple co-defendants, with the kingpin based in Chicago, having connections to organized crime. The tentacles of the drug conspiracy stretched far and wide.

Years later, a former state police CSI who worked on the Dardeen homicide case allowed me to review but not copy his notes, which indicated that Keith Dardeen had become an informant in a drug investigation by law enforcement involving kilos of cocaine.

I first heard about the Dardeen case early in my career as a private investigator. A little more than a year after the Dardeen murders, I was told by a client from Southern Illinois, who was involved in making trips to Miami in the mid-1980s, during the Miami Vice days of the Cocaine Cowboys, smuggling kilos of cocaine to Southern Illinois, not far from Ina, about a detail of the Dardeen murder that was never made public at the time he told me. My drug trafficking client informed me that Keith Dardeen’s penis had been severed after he was shot and it was stuffed in his mouth “to send a message,” he said. That conversation in early 1989 always haunted me, occurring at the beginning of my investigation of the Paris, Illinois case of Randy Steidl, who was on death row when I first met him in 1988.

The investigator for the Illinois State Police (ISP) who reached out to Texas Rangers on a hunch that Sells could be the killer of the Dardeen family had researched a newspaper article that appeared in the Sunday edition of the Evansville Courier on January 31, 1988, called “Pizza Connection Olney”, a story about Giuseppe “Joe” Trupiano, the nephew of the head of the Sicilian mafia Don Tano Badalamenti Trupiano was convicted in the largest RICO drug conspiracy case in U.S. history.

The family of Ruby Dardeen reportedly refused to cooperate with law enforcement, fearing retaliation from the mafia. I confirmed this during a phone interview with a family member in 2004, who stated, “My family would not want to get involved. We are afraid of the mafia.”

The investigation of the Pizza Connection began after FBI undercover agent Joe Pistone, known by his pseudonym “Donnie Brasco” penetrated the Bonano crime family in Brooklyn. Once inside, he discovered how heroin was being smuggled from Afghanistan through Sicily to a mob-controlled pizza parlor in Brooklyn, where it was then distributed to other pizza parlors throughout the Midwest, to small towns like Olney, Illinois, not far from Ina.

US District Attorney Rudolph Giuliani filed the charges in the Southern District of New York. The lead prosecutor, Louis J. Freeh, later became the Director of the FBI. The trial of 32 members of the American and Sicilian mafia, began on September 30, 1985, and ended more than a year later on March 2, 1987.

In the middle of that trial, in July of 1986, Dyke and Karen Rhoads were found murdered in Paris, Illinois, near the border of Indiana. A week before Karen Rhoads was killed, she told her family that over the weekend she walked in on her boss, whose business was located next to Joe’s Pizza Parlor, loading machine guns and a large sum of money in the trunk of his red corvette, headed to Chicago. At the time of the murders, one of the other defendants being tried in the Pizza Connection case in New York was Guiseppi “Joe” Vitale, from Paris, Illinois, a cousin of Joe Trupiano from Olney.

Two innocent men, Randy Steidl and Herb Whitlock had been railroaded by a local prosecutor, who subsequently resigned amid allegations of cocaine use. Through the Freedom of Information Act, I obtained a copy of an FBI report documenting that Steidl and Whitlock had provided information to the FBI that the Edgar County State’s Attorney was protecting gambling in local bars and the distribution of drugs in Paris, Illinois. Whitlock and Steidl provided that information to the FBI a few months before the Rhoads homicide and were later unjustly targeted by that same prosecutor in closing the homicide case.

During my investigation of that case, a source within law enforcement revealed to me that in March of 1999, during a federal drug trafficking investigation targeting members of the Sons of Silence motorcycle gang from Paris, Illinois, a confidential source reported that the enforcer for the gang had made statements about being involved in the Rhoads homicide. But the detail this witness gave that the victim’s penis had been severed and left in his mouth did not match the Rhoads homicide. But it did match the evidence in the homicide of Keith Dardeen, a year later, in Ina, Illinois. A crime law enforcement determined was committed by Tommy Lynn Sells.

In March of 2000, I wrote a letter to the director of the Illinois State Police, requesting a re-investigation of the Rhodes homicide case in light of information I received about the involvement of the Sons of Silence. It was also March of that year that I learned about Sells’ confession to the Dardeen murders.

Illinois State Police Lt. Michale Callahan was assigned by his director to investigate the information I provided. Later, I discovered it was the power of the media, a story being aired on CBS 48 Hours, that prompted upper management at ISP to refer my letter to Lt. Callahan, who commanded the criminal investigation unit in Champaign, Illinois. An email documented their concern about having a “Mike Wallace” type reporter embarrassing their Agency. So, rather than toss my letter into the trash, it got assigned to Callahan.

I worked closely with Callahan and his team of investigators, whose investigation focused on the remnants of the Pizza Connection RICO conspiracy case. In my investigation, I discovered that Sells and another man had rented an apartment in Coral Springs, Florida, just north of Miami in June of 1987. One of Callhan’s investigators informed me that ISP intelligence had a file on Sells, indicating that he was bringing up drugs from the Miami area during this period of time.

When I interviewed Sells on death row in Texas, I focused my questions on the Dardeen case, not wanting to tip off my interest in the Paris case of Steidl and Whitlock. I knew from my interviews of family members that Sells had attended his brother’s wedding in St. Louis on June 24, 1986, and then disappeared. This was approximately two weeks before the Rhoads homicide in Paris.

When I asked Sells about being a drug mule in Florida during that time, I asked him, where in Illinois would he deliver drugs to? He replied, Terre Haute. He described a bar there that was “members only” and he mentioned the word “mafia” to describe the “friends” he knew from that clubhouse. Terre Haute, a few miles from Paris, Illinois, is where the Sons of Silence were known to socialize.

Although he did not come out and confess to the murders of Dyke and Karen Rhoads, he told me just enough to know that he was the killer. Like the question I asked about aliases he would give police, not being in the habit of carrying identification. He replied he liked to use the names of Ricky and Richard a lot. Hours before the Rhodes murder, a man named “Richard Smith” reserved a room at the Hotel France, just blocks from the murder scene. When police went to locate him the following morning, he was gone.

I never mentioned Paris or the details of the Rhoads homicide during my interview of Sells. But after returning to my office, I received a letter from him stating, “Eifel Tower nice this time of year. Ever been?” There was no doubt in my mind that he killed Dyke and Karen Rhoads.

Sells claimed to have killed more than 70 victims, but at the time he stopped cooperating with law enforcement he told them there were more victims they hadn’t talked about.

Could Melissa Koontz be one of those victims?

The Case of Julie Rea

Sells told me that there are many more innocent people in prison because of him.

One of those people was Julie Rea, a mother who was unjustly convicted of killing her 10-year-old son Joel Kirkpatrick, a crime that happened in Lawrenceville, Illinois on October 13, 1997. Three years later, Julie was charged with capital murder based on the testimony of a discredited bloodstain expert that was presented to a grand jury. He claimed that the mother’s night shirt had evidence of cast-off patterns, suggesting that it was the mother who stabbed her child to death.

Julie Rea described being struck by an intruder after being awakened by a scream across the hall at 4 a.m. Tommy Lynn Sells would later say he dropped the knife that he used to stab Julie’s son Joel, after he was startled by the mother, otherwise, she would be dead too.

Months before Julie Rea was indicted by a special prosecutor, I was contacted by her attorney who explained that prosecutors had threatened to seek the death penalty against her client. The details of the intruder that Julie Rea described to police that her attorney conveyed sounded familiar to me.

It was June of 2000, months after I had read about Sells’ confession to the Dardeen murder. I told the attorney if I were appointed to the case, my first suspect would be Tommy Lynn Sells. I never heard back from the attorney and later learned that prosecutors had decided not to seek the death penalty in order to avoid reforms enacted by law makers and the Illinois Supreme Court intended to prevent the conviction of an innocent person facing the death penalty.

Later, I would read about Sell’s confession to the murder of Joel Kirkpatrick in Diane Fanning’s book Through the Window, the Terrifying True Story of Cross-Country Killer Tommy Lynn Sells. The confession was prompted after Fanning watched an interview of Julie Rea that aired on ABC 20/20 a few months after she was convicted of her son’s murder. She was represented by a public defender who took over the case from the private attorney who initially contacted me.

By this time, I started the Innocence Project at UIS and conducted video recorded interviews of key witnesses who placed Sells in Lawrenceville at the time of Joel’s murder. I sent the videos to John Allen of the Texas Rangers. After reviewing the interviews, Allen called to tell me that one of the witnesses had “described Tommy Lynn Sells to a T.” Ranger Allen agreed to sign an affidavit supporting a new trial for Julie Rea, convinced that Sells was the killer of Joel Kirkpatrick.

Sells provided a detailed audio-taped confession to an ISP investigator that described details that only the killer would know, yet the prosecutor who made the mistake of arresting and convicting Julie Rea refused to seek justice. After her conviction was reversed by the appellate court, she was retried, and a jury acquitted her in 2006.

The Case of Rodney Lincoln

Another innocent person who went to prison was Rodney Lincoln. He spent 36 years in prison before having his sentence commuted by the governor of Missouri in 2018. I was contacted by one of his supporters after they read my affidavit on-line that described the Dardeen murders. The victim, Joanne Tate, 35, was murdered in her St. Louis home in 1982, and was sexually assaulted in a similar manner as Ruby Dardeen, after being stabbed to death by an intruder who broke into her home around 4 a.m.

The case was featured on Crime Watch Daily in November of 2015, in which I appeared detailing the evidence that pointed to Sells. After watching the show, Melissa DeBoer, who survived having her throat slit as a 7-year-old child, posted on social media that “Rodney Lincoln did not kill my mom . . . It was Tommy Lynn Sells.”

He was only 17 when he killed Melissa’s mother.

Rodney Lincoln meeting Melissa DeBoer, who at the age of 7 witnessed the murder of her mother. Her mistaken eye-witness testimony had wrongfully convicted Rodney Lincoln three decades before their meeting in 2015 at the prison where he was confined.

I traveled to Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, where Melissa was living and she provided an affidavit describing how she was manipulated by police detectives to identify Rodney Lincoln, an ex-boyfriend of her mother, as her killer. Melissa then travelled to St. Louis at the expense of Crime Watch Daily to meet with prosecutors, and she pleaded with them to free Rodney Lincoln.

As in the case of Julie Rea, prosecutors in Rodney’s case refused to budge.

After a lengthy evidentiary hearing, the following year, a judge agreed with the prosecutor and ordered that Lincoln remain in prison. The following year, Governor Eric Greitens, ordered Lincoln’s release on his last day in office after having received a letter from film maker Ron Zimmerman, who was nominated for an Emmy Award for the two-part series he filmed for Crime Watch Daily.

According to Texas Ranger John Allen, Tommy Lynn Sells became addicted to killing people. Sells described getting the same high as sticking a needle into his veins shooting up heroin as he did plunging a knife blade into his victims and watching the life drain from their eyes, he told me during a prison interview in 2011.

Could Melissa Koontz have been one of those victims?

He is no longer alive to be interviewed. Sells was executed in 2014.

But there is one way to find out the answer to that question.

But prosecutors in Sangamon County have shown no interest in comparing the unknown male DNA from Melissa Koontz’s bra to a serial killer like Tommy Lynn Sells.

Like the other prosecutors who blocked justice for Rodney Lincoln, Julie Rea, Randy Steidl and Herb Whitlock, they seem more concerned about not admitting they made a mistake.

A Conflict of Interest

In April of 2019, an assistant state’s attorney from Sangamon County appeared before the Prisoner Review Board in Chicago to oppose McMillen’s petition alleging actual innocence. One of the members of the Board, who worked at the Sangamon County State’s Attorney’s office at the time of the Koontz homicide trial, although not directly involved with the case, recused himself, citing the appearance of a conflict of interest.

However, the Chairman of the Board, who disclosed that he was acquainted with one of the people who had testified in opposition to McMillen’s release, did not recuse himself, and voted with the other members to make a confidential recommendation to Governor JB Pritzker, who had recently assumed the office of governor. Presumably, the recommendation was to deny McMillen’s petition, which Governor Pritzker did.

The raw nerve that the case of Melissa Koontz opens up for the Sangamon County State’s Attorney is the interview I conducted accompanied by another student at the Sangamon County jail of a man who had claimed that while in custody in 1991, he overheard Tom McMillen confess to the murder of Melissa Koontz. The man admitted that his testimony was a lie that he told in order to get a break on two felony charges he was facing at the time. After testifying against McMillen, he was let out of jail and did not face prison time.

But more troubling was the revelation that the man’s request to have conjugal visits with his girlfriend was actually facilitated by employees working for the Sangamon County State’s Attorney’s office and that this sexual tryst occurred inside the Sangamon County courthouse. His account of this was corroborated by his former girlfriend.

This undisclosed benefit for the cooperation of this in-custody witness, standing alone, strongly undermines confidence in the integrity of Tom McMillen’s conviction.

A State-wide Conviction Integrity Unit

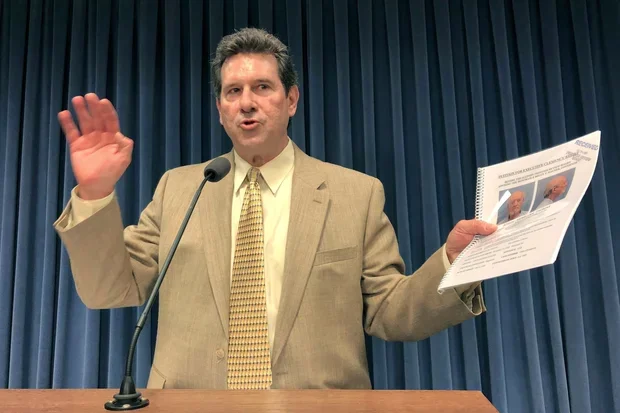

In April of 2019, prior to the hearing in Chicago, I wrote a letter to Illinois Attorney General Kwame Raoul and held a press conference at the capitol calling on him to create a state-wide conviction integrity unit, with a specific request that his office re-examine the case of Melissa Koontz’s murder. I was encouraged by a subsequent meeting I had with his chief of staff and upper-level managers, who assured me they were interested in pursuing this proposal and would formulate a plan to do so.

April 10, 2019, press conference. Story author Bill Clutter calls on Attorney General Kwame Raoul to establish a state-wide conviction integrity unit in Illinois. photo credit AP/John O’ Connor

During that meeting, I explained how former attorney general Lisa Madigan had set a precedent in reviewing the integrity of the conviction of Randy Steidl, whose case was first featured in the September 1993 edition of the Illinois Times “Wrong Man on Death Row?” By the time Madigan’s office reviewed the case in 2003, Illinois State Police Lt. Michale Callahan had conducted a thorough conviction integrity review of that case at the order of his director. Callhan’s investigation corroborated that Steidl and Whitlock were innocent. His presentation to the Office of Attorney General was persuasive in Madigan’s decision not to appeal a federal judge’s order granting Steidl a new trial.

After 17 years behind bars, Steidl was released from prison, and became the voice of the movement to abolish the death penalty in Illinois (See From death row to hero: How Randy Steidl became the face of capital punishment repeal, Illinois Times). I was seated with him when the Senate sponsor of the bill, Kwame Raoul, asked Randy Steidl to stand as he pointed toward him, declaring it was cases like his why lawmakers should cast their vote to end the death penalty.

Randy Steidl (left) with the author after the Senate voted to abolish the death penalty in 2011. He was finally released from prison after the Office of Illinois Attorney General conducted a conviction integrity review of his case.

In November of 2024, Attorney General Kwame Raoul announced the establishment of a statewide Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU), after applying for a Department of Justice grant that awarded his office $1.5 million to implement the program. In making that announcement he said the program involved five years of planning.

Finally, there is hope for Tom McMillen and Gary Eddington that they may not have to die in prison.

The Court of Last Resort

Sangamon County State’s Attorney John Milhiser should refer this case to the newly created Conviction Integrity Unit of the Illinois Attorney General with a letter transferring all prosecutorial decision-making with the AG’s office. Only then, will there be justice for Tom McMillen and Gary Edgington.

Long before Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld founded the Innocence Project, author Erle Stanley Gardner, using the profits he earned as a prolific writer of his fictional character Perry Mason, created an organization in the late 1940s called the Court of Last Resort. His team included a forensic pathologist, criminal defense lawyers and private investigators, who all worked pro bono, devoted to freeing the wrongfully convicted. Gardner collaborated with the publisher of Argosy magazine, which reported on case investigations as they progressed, in a series of articles that focused on one case at a time. With the power of the media, Gardner was able to shine a spotlight on the injustice of these cases. The court of last resort, he wrote, was “the reader of the magazine themselves.”

You, as the reader of this story, have the power to influence the Sangamon County State’s Attorney to do the right thing. As the court of last resort, let people know how you feel about this story by sharing it on social media and in conversations with friends and family. Make your voices heard!

Bill Clutter is a private investigator with offices in Springfield, Illinois and Louisville, Kentucky. He served ten years as director of investigations after starting the Downstate Illinois Innocence Project in 2001. His work on the cases of Alejandro Hernandez and Randy Steidl was credited along with attorney Michael Metnick and a handful of others by the Chicago Tribune in 2011 when Illinois abolished the death penalty.

Free The Innocent

Help Us Solve This Case